They didn’t just call it the iron lung.

They called it the last machine that could hold a child between life and death.

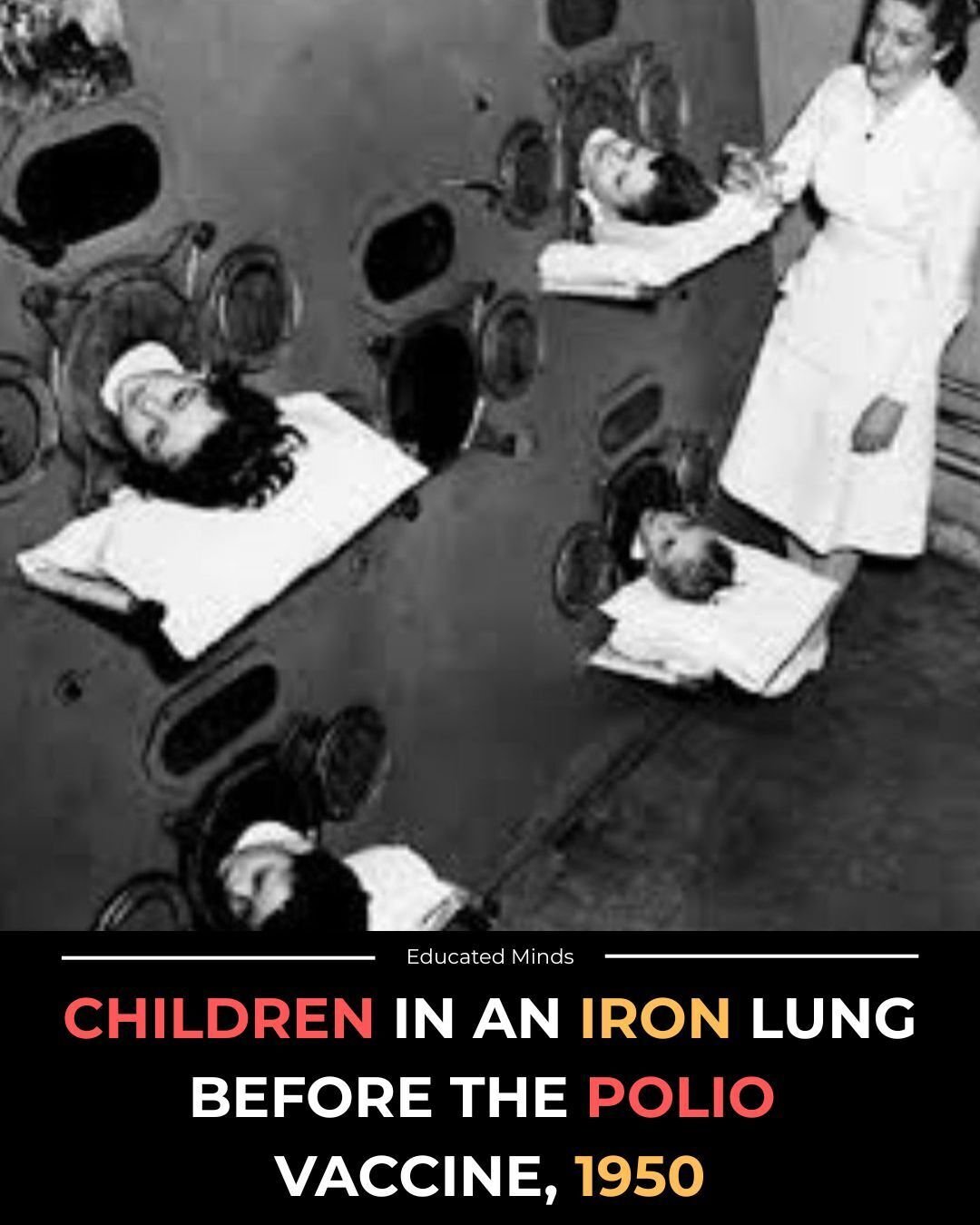

In the early 1950s, hospitals filled with metal cylinders lined in quiet rows — children inside them, staring at ceilings they couldn’t touch, breathing through a rhythm they didn’t control.

When polio stole a child’s muscles, it stole the chest first.

The lungs stopped rising on their own.

And so these machines rose and fell for them, the hum of the motor becoming the heartbeat of entire wards.

Parents stood at the edge of steel chambers, speaking through small mirrors angled toward their child’s eyes.

Nurses learned to read emotions from tiny movements — a nod, a tear, the twitch of a lip.

Some children lived in these chambers for weeks.

Others measured whole seasons in the sound of metal expanding and collapsing.

Polio was unpredictable — a shadow that crossed playgrounds, swimming pools, summer camps, entire neighborhoods.

Every year it paralyzed thousands.

Every year it took something childhood was never meant to lose: the freedom to breathe without fear.

Then came Jonas Salk.

A vaccine that didn’t ask for money, fame, or ownership — only trust.

Within a single generation, the iron lung went from a necessity to a relic.

A simple shot replaced a room full of machines, and the world stepped out of a nightmare it had lived in for decades.

Fun Fact:

The number of Americans using iron lungs fell from over 1,200 in the 1950s to fewer than 10 today.

Because this image isn’t just about disease.

It’s about distance — the reminder of how far science can carry us when one breakthrough rewrites the fate of millions.